The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

Bruno

Richard Hauptmann's

Extradition

![]() Hauptmann's

Connection with the Aldinger Family

Hauptmann's

Connection with the Aldinger Family

![]() Read a

Debate about the legality of the Bronx extradition hearings

Read a

Debate about the legality of the Bronx extradition hearings

![]() Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

![]() Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

![]() Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

Hauptmann Should Not Have Been Extradited

Michael Melsky

Posted on the

LKH Public Forum

Wed Aug 29 2001

Lets put these sick events in order:

A *New York Times* article quotes Foley as saying: "...the employment

records showed that Hauptmann quit work at the Majestic at 1p.m. the day of the

kidnapping". And quoted Wilentz as saying: "The police know definitely

that Hauptmann did not work those hours, nor did he put in a full day of work on

March first..." (Scaduto 282).

Fawcett filed the original Writ of Habeas Corpus in October because he saw the

timesheet indicating Hauptmann worked on 3-1. When Morton ignored the Subpoena,

thereby risking Contempt of Court, and the coverup begins...

In order to ruin Hauptmann's alibi that he was working on 3-1, Reliant Property

Management, Assistant Treasurer, Howard Knapp testifies. Unbelievably, he

testifies that those payroll records (ending Mar 15th.) do not exist.

"Our records,....."do not indicate that any such records exist at this

time..."or at that time either" (Kennedy 223).

After these obvious lies, Hauptmann and Fawcett lose the hearing. Fawcett,

knowing that the timesheets ending March 15th will prove Hauptmann worked on the

1st, files an appeal which stays the extradition.

As a result of Knapp's testimony, Joseph Furcht, who was Superintendant of

Majestic and Hauptmann's boss, was tracked down. Furcht writes an affidavit

which says in part:

and worked throughout that entire day until 5 p.m., subsequent thereto they

worked there the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th days of March 1932 from eight o'clock in the

morning until 5 p.m. in the afternoon. proving what Fawcett already knew and

tried to prove at the hearing - that Hauptmann worked on March 1st. Furcht

attaches a copy of documentation proving employment on the 1st to the affidavit.

Additionally, E.V. Pesia, the Employment Agent verifies Hauptmann's employment

on the 1st.

Fawcett files his appeal based on this evidence concerning Furcht and Pecsia.

Wilentz appears before the press and says: "The police at no time were in

possession of the payroll..." (Kennedy 226)

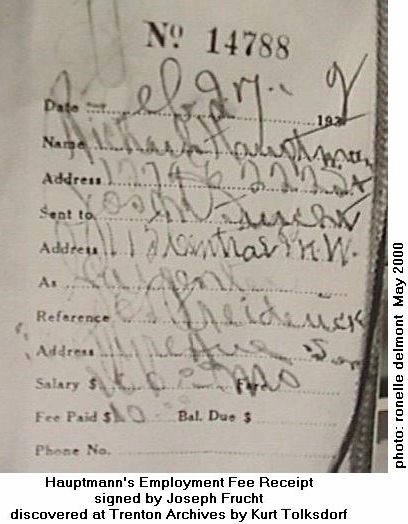

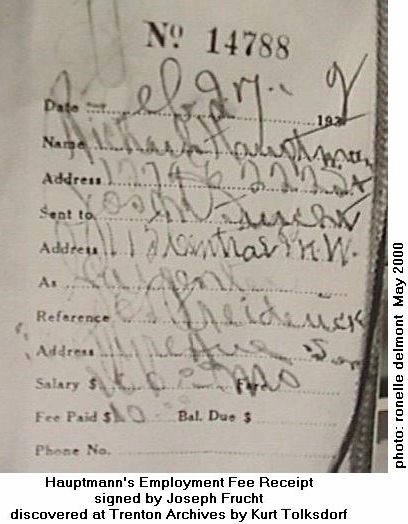

We know this was a lie because of the receipt Scaduto found:

10-29-34 Receipt from NYPD:

Received from Asst. District Attorney Edward Breslin, the following enumerated

records, to be used in the case of the State of New Jersey vs. Richard B.

Hauptmann:

(omit)

1 Carbon copy of payroll for period ending March 15, 1932

Signed for by Detective Cashman and winds up with Inspector Walsh.

Oct 19th, Fawcett's appeal is denied by Bronx Appeal Court Five Judge Panel, and

the Writ of Habeas Corpus dismissed.

The reason for this is:

The new evidence was in conflict with evidence already heard, they said, and

issues of fact should await the trial of the action (Kennedy 226)

So Knapp's perjured testimony is what made Hauptmann extraditable. Without it,

there would have been no extradition and Hauptmann would have remained in NY on

extortion charges...

On Oct 23rd, Furcht is brought to a "closed door meeting" with Wilentz

and produces a second affidavit. VDers say what you will, but the important part

is:

If I were to refer to this book as of March 1, 1932, it would be possible for me

to determine whether or not the particular workman worked a full day...I do not

know whether or not those records are still available, but they were when I left

in December 1932.

So in just a few short days, Furcht was "worked over" into casting

doubt on his previous statements by Wilentz...sound familiar? But looking at the

important part, you can see where Furcht's heart is. Too bad he never was called

to testify. They were never able to "turn" Pescia though and he stuck

to his statements throughout...

See his letter posted on this website made

available by Ronelle @ http://www.lindberghkidnappinghoax.com/pescialetter.html

Lets not forget that the Furcht/Pescia documentation attached to the original

Furcht Affidavit also "disappears".

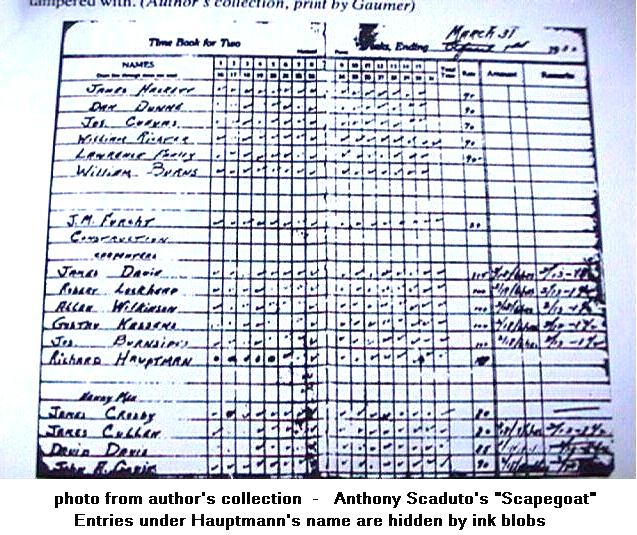

BTW...Morton's Trial Testimony (p.1906):

Q: While you are here does your book include the time from March 1st to the

15th?

A: It does.

posted

on the LKH Public Forum

Sat

Aug 18 2001

Kidnapping

March 1st - Money delivered April 2nd.

It

was Hauptamann's position when arrested, that he worked on 3-1-32.

According

the supervisor of construction, Joe Furcht, as well as employment agent E.V.

Pescia, Hauptmann worked a full day 3-1-32. Furcht made a sworn statement to

this fact and attached a copy of the paysheet to it. Of course this paysheet

vanishes after being turned over to Inspector Harry Walsh. The records that were

not missing were clearly tampered with as indicated by Kennedy and Scaduto. Both

the time book and the payroll time record shown in Kennedy are clearly altered.

You can't look at them and tell me they aren't.

Howard

Knapp, assistant treasurer for Reliance Property Management, testified at the

Bronx hearing testified that the records for March 1st to 15th "do not

exist".

10-29-34

Receipt from NYPD:

1

Employment Card for Richard Hauptmann

1

Employment Card for John Fordyce

1

Carbon copy of payroll for period ending Feb. 29, 1932

1

Carbon copy of payroll for period ending March 15, 1932

1

Carbon copy of payroll for period ending March 31, 1932

1

Carbon copy of payroll for period ending April 15, 1932

The

above records are property of the Majestic Apartmanets, 72nd St. and Central

Park, West, New York City.

Scaduto

quotes a Times article quoting Foley as saying: "...the employment records

showed that Hauptmann quit work at the Majestic at 1p.m. the day of the

kidnapping". And quoted Wilentz as saying: "The police know definitely

that Hauptmann did not work those hours, nor did he put in a full day of work on

March first..." (page 282). Thereby proving their knowledge of records that

Knapp had testified "did not exist".

Kenndey

referencing Agent Seykora's report, indicates that while at Reliance Property

Management Company, where they were referred to the owners, they saw a Mr.

Birmingham. Birmingham indicated that Hauptmann's employment ended on April 2nd.

He also indicated that Hauptmann was working on April 2nd. (page 185-86

paperback)

Morton

(Reliance time keeper)direct by Wilentz page 1905:

Q:

On April 2nd, 1932 tell me whether or not Bruno Richard Hauptmann worked.

(Objection

Pope)

(omit)

A:

No, sir; Bruno Richard Hauptmann did not work on April 2nd, 1932.

Morton

cross by Reilly page 1913-14

Q:

Then you have a check that he (Hauptmann) worked on the 3rd and 4th, haven't you

A:

Yes, sir. (omit) Q: What day was Sunday? A:

April 3rd.

Q:

Did any carpenters work on Sunday? A: No. (omit)

Q:

26th. Now, every one of the carpenters on the 26th of March, which you claim was

a Sunday, have check marks opposite their names just as though they worked,

haven't they? A: Yes, sir.

Q:

And April 2nd, carpenters, you have an "O," is that right?

A:

For the carpenters.

Q:

Yes, a naught for Hauptmann? A: Yes, sir.

Q:

But you have a check marked the next day, April 3rd, haven't you?

A:

Yes, sir.

Q:

He didn't work that day, did he? A: No, sir; he didn't. (omit)

Q:

Then you don't keep your books accurate, do you?

A: Yes, sir. Q: You think that is accuracy, do you?

xtradition Debate From the Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax Forum

Michael

Donner

Hauptmann's extradition

Thu Feb 21 2002

I read a post down a little ways that if New Jersey had not produced Whited at

Hauptmann's extradition hearing to place Hauptmann is New Jersey on March 1,

1932, then Hauptmann could not have been extradited. (I don't know who wrote it;

y'all use so many fake names today I can't identify you!). However, I do not

think that the assertion about Whited's testimony is correct.

It is true that not being in the demanding state at the time the crime was

committed is a defense to extradition. However, the burden of proof at the

extradition hearing was on Hauptmann to show, clearly, convincingly, and

conclusively that he was not in New Jersey on March 1, 1932. Please note where

the burden lay; this is important, because only Hauptmann had the burden of

producing evidence at the extradition hearing. In other words, New Jersey did

not have to prove that Hauptmann was in Hunterdon County on March 1, 1932.

Hauptmann had to prove that he wasn't there. New Jersey could (and did) produce

evidence that Hauptmann was there, but that was merely to rebut Hauptmann's

evidence.

Hauptmann testified himself at the extradition hearing; and produced Christian

Fredericksen and Kate Fredericksen, Anna, and Howard James Knapp as witnesses.

Hauptmann gave the following account of his whereabouts on March 1, 1932:

On the Monday night preceding he slept at his home at 1279 East 222d street,

Bronx, New York City. He awakened at 6 on the morning of Tuesday, March 1, 1932,

and at a quarter to 7 took his wife by automobile to the bakery store at 3815

Ryder avenue, Bronx, where she worked. He then took his automobile home, which

took about two minutes, and went to the Hotel Majestic, Central Park West and

Seventy-Second street, Manhattan, or to the employment agency on Sixth avenue

looking for a job. He was not sure which. He stated he went to the agency and

from there was sent to the hotel, around the 1st of March, 1932, the end of

February, or early in March around the day in question. During 1929, 1930, and

1931 he worked steadily as a carpenter, but not in 1932. If he worked at the

hotel, he quit at 5 o'clock, or, if not, he was at the agency all day. He then

went home, changed his clothes, and went down to the bakery and met his wife,

getting there between 6 and 7, where he had his supper.

On cross-examination, Hauptmann did not fare well, coming across as not really

being sure WHERE he was at any given time, and certainly not clear when he began

and ended his employment at the Majestic:

'Q. What day did you quit your employment with the Majestic Hotel? A. I don't

know.

'Q. You don't know? A. No.

'Q. Nothing at all about the time to refresh your recollection? A. It must be in

April.

'Q. In April--how long did you work for this Majestic Hotel Company? A. I cannot

remember.

'Q. When you were arrested, you answered that you worked there from February

right through steady every day, right through until April, didn't you? A. Yes,

but after thinking, I am not quite sure.

'Q. Well, that is not correct then, is it--you did not work there from February

till April, did you? A. I cannot answer.'

Christian Frederickson and his wife, while testifying that Hauptmann

"usually" met and picked up his wife on Tuesday night, certainly did

not help Hauptmann out. Christian stated:

"He usually called for her always on Tuesday nights and Friday nights. . .

I say usually--I cannot swear he was there every week."

His wife was even less helpful, stating that she could not say whether Hauptmann

was at the store or not on March 1, 1932 because she wasn't at the store that

evening.

Anna testified that Hauptmann picked her up from the bakery on March 1, 1932,

but she also admitted that she had originally told police she had no idea

whether Hauptmann had picked her up that night; it was too long ago for her to

remember.

I think even that if NO New Jersey witnesses had testified, Hauptmann would have

failed to carry his burden of showing by clear and convincing evidence that he

was not in New Jersey on March 1, 1932.

Finally, at least to the reviewing court, it was not Whited's testimony, but the

handwriting testimony and evidence, that tipped that balance in New Jersey's

favor. Apparently Hauptmann's counsel did a good job challenging Whited's

credibility. The court stated:

"Bearing in mind the rule that evidence should be construed liberally in

favor of the demanding state, the [handwriting samples] in my opinion for the

purposes of this hearing constitute admissions of the presence of [Hauptmann] in

New Jersey at the time of the commission of the crime. The testimony of the

witness Whited may be weakened by the attack made on his credibility, but,

considered by the same rule, it adds to the weight of the admissions showing

presence. . . My conclusion is that [Hauptmann] has not conclusively established

that he was not in the demanding state at the time it is charged the crime was

committed."

I don't think Hauptmann's evidence met his burden of proof even WITHOUT New

Jersey's evidence.

So, the conclusion that I reach is that Hauptmann would have been extradited

even WITHOUT Whited's testimony.

Michael Donner

NJ evidence

Thu Feb 21 18:19:53 2002

New Jersey produced handwriting evidence (including the nursery note, linked to

Hauptmann through Osborne's testimony) and the testimony of Whited to show

Hauptmann was in NJ on May 1, 1932.

Now, easy! I know what the opnion of most on this board is about the quality of

this evidence. I agree with you; I also agree that ONLY the nursery note is

relevant as to the question at issue at the extradition hearing: whether or not

Hauptmann was in Hunterdon County on March 1, 1932. I also agree that Whited was

lying. However, in focusing on New Jersey's evidence, you miss the point. That

focus is proper relating to the TRIAL. But, recall, at the extradition hearing,

the burden of both production and persuasion was on Hauptmann. So, it is to the

quality of HIS evidence that you must turn (again, this is for the extradition

hearing ONLY).

The question, as far as the extradition hearing was concerned, was: did the

evidence produced by HAUPTMANN prove clearly, convincingly, and conclusively

that he was NOT in NJ on March 1, 1932? Indeed, he testified that he was not

there. However, all his other alibi witnesses (including his wife!) admitted

that they could not remember that night in particular (Anna, on

cross-examination, and Christian on direct); and one (the bakery owner's wife)

admitted that she was not even at the bakery that evening. Look particularly at

Hauptmann's testimony on cross-examonation as to when he worked at the majestic.

Too many "I don't know" and "I can't say" to make his

testimony appear relaible. Can anyone say, sitting as a judge at that hearing,

that Hauptmann proved to you clearly and convincingly that he was not in New

jersey on March 1, 1932?

Heap your derision on Whited and Hochsmuth for their trial testimony, and I will

have no disagreement with you. Question the sufficiency of the evidence at trial

for the capital murder charge (i.e., the predicate felony of larceny), and I am

in full agreement with you. In my opinion, I think Hauptmann was guilty only of

extortion.

This post is simply directed at the assertion that Whited was critical for

Hauptmann's extradition. I am pointing out that Whited's testimony was not

critical at the extradition hearing; the court clearly discounted it; and

Hauptmann clearly would have been extradited without it.

Clubbeaux

Yes, you're right.

Thu Feb 21 2002

So what would have cleared Hauptmann at the extradition? Maybe something his

attorney, Fawcett, could have gleaned from the Bronx Grand Jury hearing. He

never had that chance, however, since Judge Henry Stackell prevented Fawcett

from having access to the minutes. The Grand Jury, it will be remembered, allows

access to its indictment proceedings. There was no reason to prevent Fawcett

access, except to grease the railroad tracks.

The work

records from the Reliance would have proved that Hauptmann worked a full day

at the Majestic March 1st. Fawcett subpoenaed both the records and Morton, the

timekeeper. The State managed to both confiscate the records (they turn up later

when Cashman signs for them from Breslin, for the receipt see Kennedy, p. 223)

and prevent Morton from attending, sending some poor flunky named Knapp along,

who was told to insist that those particular timesheets did not exist “at this

time, or at that time either.”

Nevertheless Fawcett obtained a 48-hour stay, during which time Tom Cassidy

found Furcht, who furnished the records that proved Hauptmann worked a full day

March 1st. The records were destroyed, however, and Hauptmann was extradited.

Michael Donner

Question

Thu Feb 21 2002

Let me ask you a question that has always puzzled me about this case.

Hauptmann's defenders claim that he worked an entire day at the Majestic on

March 1, 1932. I'm assuming a full day's work ended at 6:30 p.m. or so, when it

starts to get dark. The child was kidnapped around 9:00 p.m. or so, right? So,

even if Hauptmann worked a full day on March 1, 1932, wouldn't he still have had

time to drive to Hunterdon County and get there by 9 p.m.?

Your other point is well taken; if Hauptmann's defense was denied access to

records that would have proven his innocence, then that is indeed a travesty.

Clubbeaux

The timing

Thu Feb 21 2002

Actually he worked from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Still it would have been almost

impossible for him to take the subway back uptown -- the Majestic's in mid-town

Manhattan on the park side, if memory serves, and Hauptmann lived way up in the

Bronx, that's a hefty ride -- stash the ladder in the car and drive through rush

hour traffic to Hopewell, park the car in the necessary place, hide himself,

etc. It probably could have been done, but it certainly makes for a much weaker

case to suppose that it was done.

You do know the story of the

Furcht Affidavit and the Morton/Knapp timesheets, right? Of course records

were destroyed.

Michael Melsky

I Don't Think So

Thu Feb 21 2002

I will try to make this as clear as possible....

Burglary is inserted into this case because its element was necessary at the

time in order to prove murder in the first degree -

Hunterdon Oyer and Terminer September Term, A.D., 1934

HUNTERDON COUNTY, ss.:

THE GRAND INQUEST for the State of New Jersey in and for the body of the County

of Hunterdon, upon their respective oaths Present, that Bruno Richard Hauptmann,

on the first day of March in the yeard of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and

thirty-two, with force and arms, at the Township of East Amwell, in the County

of Hunterdon aforesaid and within the jurisdiction of this Court, did willfully,

feloniously and of his malice aforethought, kill and murder Charles A. Lindbergh

Jr., contrary to the form of the statutes in such case made and provided, and

against the peace of this State, the government and dignity of the same.

ANTHONY M. HAUCK, JR.

Prosecutor of the Pleas

Section 36 of the Criminal Procedure Act of New Jersey provided in 1935:

...it shall be sufficient in every indictment for murder to charge that the

defendant did willfully, feloniously and of his maice aforethought, kill and

murder the deceased.

Killing equals murder when:

Sections 106 and 107 Crimes Act-

#1 Perpertration or attempt to perpetrate arson, burglary, rape, robbery, or

sodomy.

#4 Willful, deliberate and premeditated killing;

#5 By means of poison, or by lying in wait.

See State vs. Wyckoff, 31 N.J. Law 65, decided by Chief Justice Beasley in 1864

Where it was ruled:

The general rule of the law has always been that a crime is to be tried in

the place in which the criminal act has been committed. It is not sufficient

that part of such act shall have been done in such place, but it is the

completed act alone which gives jurisdiction. So far has this strictness been

pushed that it has been uniformly held, that if a felony was committed in one

county, the accessory having incited the principal in another county, such

accessory could not be indicted in either.

Unless Hauptmann is guilty of killing the baby while committing Burglary, then

he could only be guilty of second degree murder....

The actual presence of Hauptmann within the State of New Jersey would be

necessary at the time or day of the commission of the crime, under New Jersey

law at the time, to find him guilty of murder. The ladder, ransom notes, and

ransom money doesn't do this. This is where the bogus testimony of Whited and

Hockmuth comes in....

Opening statements (TT p1):

[Wilentz]- May it please your Honor Mr. Foreman, men and women of the jury, a

Grand Jury that was composed of citizens of this County has returned an

indictment charging that Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr., was murdered. It is the law,

men and women, as will be pointed out to you by the Court, that where the death

of anyone ensues in the commission of a burglary, that killing is murder,

-murder in the first degree.

Burglary was defined in two New Jersey Statutes:

P. 1787, Section 131 - P.L. 1898 p 830

Or as defined by Common Law...(See State v. Wilson 1 N.J. Law, 439)

Legal Aspects of the Trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann

by Frederick C. Vonhof, Counsel for the "Independant Press"

January 1935

Why Hockmuth and Whited?

....from the case of State v. Wycoff ....This undoubtedly accounts for the

presentation of the testimony by Hochmuth and Whited placing Hauptmann within

this State prior to the commission of the act and also on the date in

question......Hauptmann's actual presence is necessary within the State of New

Jersey at the time or day of the criminal act in order to find him guilty of

murder ......in the State of New Jersey.

(omit)

If then, the accessory by the common law was answerable only in the county in

which he enticed the principal. and that, too when the criminal act was

consummated in the same county, it would seem to follow necessarily in the

absence of all statutory provision, that he is wholly dispunishable when the

enticement to the commission of the offence has taken place, out of the State in

which the felony has been perpetrated. Under such condition of affairs it is not

easy to see how the accessory has brought himself within the reach of the laws

of the offended State. His offense consists in the enticement to commit the

crime; and that enticement, and all parts of it , took place in a foreign

jurisdiction. As the instrumentality employed was a conscious guilty agent, with

free will to act or refrain from acting, there is no room for the doctrine of a

constructive presence in the procurer. Applying to the facts of this case the

general and recognized principles of law, it would seem to be clear that the

offense of which the defendant has been guilty is not such as the laws of this

State can take cognizance of. We must be satisfied to redress the wrong which

has been done to one of our citizens, and to vindicate the dignity of our laws

by the punishment of the wrong-doer who came within our territorial limits.

As for the defendant, who has never been, either in fact or by legal

intendment, within our jurisdiction, he can be only punished by the authority of

the State of New York, to whose sovereignty alone he was subject at the time he

perpetrated the crime in question.

Michael Donner

Re: I Don't Think So

Thu Feb 21 2002

I'm not sure where you are going with your discussion . .. several months ago I

posted my conclusions on what the jury could have legitimately concluded,

provided they believed all the evidence that the state presented.

Now, for all you out there that think the evidence was rigged, don't get angry

:) All I'm doing is determining as a matter of law what the jury COULD have

found Hauptmann guilty of, if they believed the evidence. It's a "worst

case" scenario: even the worst case scenario shows that Hauptmann should

not have been executed.

So, here goes the short version- and for those of you who at the mention of the

ladder and handwriting evidence go ballistic, I apologize in advance :)

The jury could have found from the evidence that Hauptmann was at the scene of

the crime in Hunterdon county on March 1, 1932. Evidence: (1) The ladder with

the rail from his attic; (2) the nursery note handwriting testimony, which was

the most damning, because it put him inside the nursery; (3) the eyewitness

testimony that Hauptmann had recently been in the area near the scene of the

crime.

The jury could have found from the evidence that Hauptmann kidnapped the child.

Evidence: reasonable inferences from the evidence listed above. Hauptmann was in

the nursery and left a ransom note. It's reasonable to infer that he kidnapped

the child.

The jury could have found that Hauptmann killed the child. This is a more

difficult call. Where is the evidence that Hauptmann struck the fatal blow? If

we rely upon the inexpertly-performed autopsy, the child died from a blow to the

head. Where is the evidence that Hauptmann delievered the blow? Where is the

murder weapon? Where is Hauptmann's connection to the fatal instrumentality?

But, Hauptmann's lawyer's job at this point was to develop some alternative

scenario that could account for the child's death, given the evidence.

Circumstantial evidence must support the inference of guilt beyond a reasonable

doubt, and simultaneously exclude any hypotheses of innocence that flow from the

evidence. Given that the evidence supported the inference that Hauptmann

kidnapped the child, the lack of any inferences supporting a hypothesis of

innocence, and the fact that the child was indeed struck a fatal blow, I think

that the inferences from the evidence supported the verdict that Hauptmann

killed the child.

At this point, we are at second degree murder.

In order for the state to get the death penalty, it had to prove that the murder

took place during the commission of a burglary. Note there are two elements

here: (1) a substantive element; i.e., Hauptmann committed a burglary; and (2) a

temporal element; i.e., the fatal blow was struck DURING THE COMMISSION OF the

burglary. I find the state's evidence insufficient to support either element.

First, the substantive element. Murder in the commission of a kidnapping was not

a capital crime in New Jersey in 1932. The prosecution had to prove murder in

the commission of a burglary. Burglary at common law (statutory burglary is

slightly different but its elements are sufficiently similar for this

discussion) is breaking and entering a dwelling place in the nighttime with the

intent to commit a felony in the dwelling. The intent to commit the felony must

be formed PRIOR to the breaking and entering. The state postulated (and the jury

found) that Hauptmann formed the intent to steal the child's sleeping suit prior

to his breaking into the house. Where is the evidence to support that? True, he

sent the child's suit as "proof" the child was alive, but it is just

as reasonable to assume that he formed that intent to take the suit AFTER entry.

In my last post on the subject, I noted that it was interesting indeed that

Hauptmann would have escaped the electric chair had the Eaglet gone to bed naked

that night. Incredible, but true. Without the theft of the sleeping suit, there

was not larceny. With no larceny, no burglary. No burglary, no death penalty.

Second, the temporal element. The blow must have been struck IN THE COMMISSION

OF the burglary. Practically speaking, the prosecution had to prove the child

was murdered in the room, going down the ladder, or shortly after the get away.

There is NO (and I repeat, NO) evidence that proved that the child was killed

during the kidnapping. From the evidence adduced at trial, why is it not as

reaosnable an inference that Hauptmann took the child back to NY, and one month

later the child fell and hit his head, and Hauptmann drove back to NJ to hide

the body? It is the lack of evidence concerning this temporal element of the

felony murder charge that troubles me the most about this case. The evidence

that Hauptmann committed second degree murder was there (as much as we may tend

to disagree with it). The evidence that he committed felony murder was wholly

lacking. I think that it was a miscarriage of justice that the New Jersey

appellate courts did not overturn the felony murder conviction on that ground

alone. I find it incredible that Hauptmann's lawyers did not ask for an

instruction on 2nd degree murder. Perhaps they did; I have never seen the entire

transcript of the trial. If they didn't ask for that "lesser included

offense" instruction, they were negligent.

At any rate, I hope this post was responsive to what you were trying to point

out.

Michael Donner

Extradition

Sat Feb 23 10:16:36 2002

Actually, federal law controls at an extradition hearing. Extradition of a felon

from one state to another is covered in the U.S. Constitution, and a federal

statute implements the Constitutional imperative. So, the controlling law is

federal law. When I said "NJ evidence", i was talking about the

evidence that NJ presented, not the controlling law.

Hauptmann tested the legality of his extradition (actually, his concinued

incarceration after the hearing) by filing a petition for a writ of habeas

corpus in the NY Supreme Court (which is the TRIAL court; for some reaosn, NY

calls its trial court the SUPREME court). The habeas court (the trial court)

reviewed the record of the extradition hearing and found Hauptmann's evidence

that he was not in NJ on March 1, 1932 insufficient. The court also, in dicta,

really, discussed the evidence submitted by NJ.

So, to answer your first question: becuase the extradition was reviewed pursuant

to a petition for habeas corpus, the initial "reviewing" court was

actually the trial court. The trial court's decision, upholding Hauptmann's

extradition, was then appealed to the NY Supreme Court, Appellate division,

which affirmed the trial court's judgment.

van Henke and Kiss did not testify at the extradition hearing, probably because

Hauptmann's counsel either did not know who or where they were. That happens

often; the preliminary matters in court often exclude very important

witnesseither becuase the prosecutor does not want to "tip his hand"

or because the defense hasn't had the opportunity to find them yet.

Yes, both the trial court's habeas review and the appellate court's review are

published opinions.

Please visit :

![]() Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

![]() Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

ronelle@LindberghKidnappingHoax.com

![]() Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

© Copyright Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax 1998 - 2020