The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

The Ransom Money

Directory Books Search Home Transcript Sources

![]() Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

![]() Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Exclusive! Lindbergh Family Secret Never Before Revealed

Great Grandfather, Dr. E. A. Lodge, Manslaughter Trial - 1862

Elmer Irey's Story JJ Faulkner LKH Forum Debates

On April 5, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an Executive Order requiring that all gold and gold certificates be returned to banks.

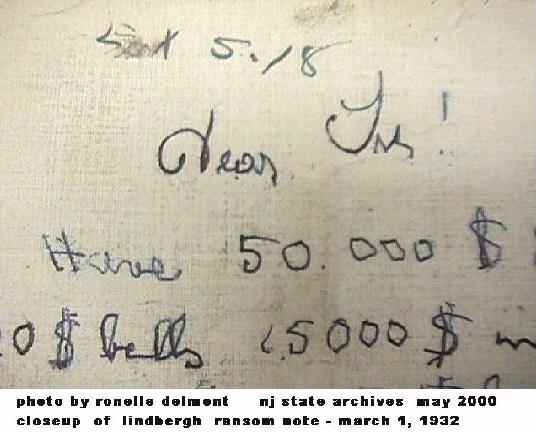

Forty thousand dollars of the Lindbergh ransom money had been paid in gold certificates. Elmer Irey, ( 1899 - 1948) an agent from the U S Treasury Dept. had to talk Charles Lindbergh into allowing the ransom note serial numbers to be recorded before payment would be made to the supposed kidnappers. Lindbergh had staunchly refused to have this done even though it would not have, in any way, affected the welfare of his child.

All gold certificates had to be turned in by May 1, 1933 and anyone who would not do so would face 10 years in jail or a $10,000 fine, or both. Banks in New York City were informed on May 23, 1932, to be on the lookout for the ransom certificates.

Three days later, the NJ State Police offered a reward of $25,000 for information that could lead to the arrest of the kidnappers.

Later, a pamphlet was given out to every employee handling currency in banks, grocery stores, insurance agencies, gas stations, airports, department stores, and post offices. The pamphlet warned everyone to watch for any ransom certificates and gave the serial numbers of each certificate.

Pins were put on an enormous map to symbolize where each ransom bill was found. The authorities pin pointed the kidnappers to the Bronx.

On Monday, April 4, 1932, a twenty-dollar ransom bill was deposited in a branch of the East River Savings Bank in Manhattan by a David Marcus who was later cleared by investigators.

But, on November 26, Hauptmann's birthday, a cashier named Cecile M. Barr, was working at the Loew's Sheridan Square Theater. She began counting the receipts of the night's business. Then, according to Barr, a folded bill was thrown on the counter. A man in his mid-thirties stood before her. She asked what price ticket he wanted - there were three different prices. The man said "One forty" and Barr gave him a ticket.

The next day the assistant manager of the theater took the money to the bank. The bank teller on duty at the Corn Exchange Bank, William Cody, discovered that the bill Barr received by the mysterious man was a ransom bill.

Barr was then shown the bill, but this time the folded bill was in the hands of a Lieutenant Finn. Barr described the man as best as she could. He was medium in height and weight. He wore a dark suit and hat. He had blue eyes, high cheekbones, and flat cheeks. His face was triangular and his chin pointed. Her description fit that of Cemetery "John."

On September

5, the National Bank of Yorkville turned up another Lindbergh ransom

certificate. The bill was deposited by a grocery store. A man from the grocery

store said that a male paid for a six-cent purchase with the ten-dollar

certificate. He would not have taken the certificate which he knew was to be

returned long ago, but business was bad. He described the man as best as

possible- the description matched that of John.

Yorkville. Another bill was given to

Chase National Bank on September 8. The bill was traced back to the Exquisite

Shoe Store. The cashier on duty, Albert Shirkes, said that a male purchased a

pair of women's black suede shoes for $5.50. A description of the man again

pointed to John.

Bills began to turn up at a rapid pace. Calls were coming in daily, each claiming another ransom certificate was found. The police were sure of one thing- the person using the bills kept paying for small purchases with big bills. The map continued to fill with pins. The police felt confident an arrest would soon occur.

Only $5,100 of the $50,000 was found before the search of Hauptmann's garage. The ransom money found in Hauptmann's garage, $14,600, was the key evidence that got Hauptmann extradited to NJ.

The problem in this case is that over $30,000 of the ransom certificates has never been.

So, where's the money?

``If it had not been for your service being in the case, Hauptmann would not now be on trial and your organization deserves full credit for his

apprehension.''

Excerpt from Charles Lindbergh's letter to the Internal Revenue Service.

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax Forum Debates

Clubbeaux

That Reasonable Doubt

Fri Feb 22 2002

I'll say that the issue of Hauptmann's employment is troubling to me, but not so

troubling as the fact nobody – not Wilentz nor anyone since – has ever

proven the Fisch story wrong; or really has done anything more than snicker at

its name. Here in America the burden of proof is on the prosecution, it’s not

impingent on you to prove your alibi is true, it’s the job of the prosecution

to prove it’s not – and now documents show that the “Fisch story” was

not so fishy after all. Tom Zito did a good job in Life recounting it:

Business ledgers confiscated by the police and never introduced in court

established that Fisch and Hauptmann were indeed business partners. Nobody

doubts this today, but bear in mind that during the trial Wilentz managed to

convince the jury they weren’t. Further supporting evidence could have been

supplied by police files – references to letters written by Isidor Fisch’s

friend and roommate, Henry Uhlig, that were also confiscated by the police and

never introduced in court. A New Jersey State Police file discovered in the

early 1980s refers to a letter Uhlig wrote to a friend in Germany the day before

Hauptmann’s arrest, in which he claims that Hauptmann had loaned Fisch $7,500

and states that Fisch “had been swindling people.” After Uhlig learned of

Hauptmann’s arrest, according to another state police document, he wrote a

letter stating that Fisch had “bought some hot money and gave it to Hauptmann.”

Uhlig added, “Now the poor man is going to have to pay.”

Also unavailable for Hauptmann’s defense was a letter written to him by

Isidor’s brother from Germany shortly after Isidor’s death and later

confiscated from Hauptmann’s home by police. Pinkus Fisch wrote to Hauptmann

of his brother’s death: “I feel it is my duty to let you know about it

in America as my brother has often talked about you and your business

connections with him… in his last few hours he mentioned your name and I

suppose he wanted to say something to us about you, or

something for us to tell you, but he did not have the strength….”

Hauptmann well understood the importance of this letter as evidence to support

his case. A New Jersey State Police report on the secret and illegal

surveillance of Hauptmann in his jail cell has the prisoner saying to his wife,

“If Isidor Fisch had not died in Germany, I would not be here behind bars.

Have you the letter from Fisch’s brother?” Anna Hauptmann responds that the

police have taken it.

Other documents also support Hauptmann’s contention that he had not known

about the ransom money, let alone spent any, until shortly before his arrest.

Lindbergh ransom bills discovered between 1932 and the summer of 1934 almost all

shared similar characteristics. New York police files contain lab reports of all

known ransom money passed in the city, showing that most of those bills bore

traces of lipstick and mascara, not to mention microscopic traces of gold or

brass particles. Moreover, the bills were folded repeatedly so as to fit into a

small watch or vest pocket. The half dozen or so ransom bills known to be passed

by Hauptmann bore no resemblance to bills passed earlier. No lipstick traces. No

gold or brass particles. No folds of any kind. Furthermore, they all showed

evidence of being waterlogged, consistent with his testimony of the saturated

shoe box.

Perhaps even more interesting, a magazine report published shortly after

Hauptmann’s arrest refers to Lindbergh ransom money cashed in by Isidor Fisch

to buy his boat ticket to Germany.

In its December 31, 1934, issue Time

magazine, summarizing evidence that would be brought forward by the prosecution

against Hauptmann in his trial, wrote, “Isidor Fisch, Hauptmann’s partner in

random business ventures, used ransom money to pay for his passage back to

Germany, where Fisch died of tuberculosis in 1933.” Yet this fact was never

mentioned by the prosecution during the trial.

The reason: police evidently believed at the time that the $2,000 in Lindbergh

bills cashed by Fisch was the same $2,000 that Hauptmann had told them he had

loaned to Fisch the day he sailed for Germany. The money seemed to constitute

important evidence against Hauptmann. Only later was it discovered that Fisch

had cashed the ransom money several hours before Hauptmann withdrew $2,000 from

his bank account to give to his friend. The implication is clear: Hauptmann had

been telling the truth, and it was Fisch, not Hauptmann, who had the ransom

money in 1933.

G. Willikers N. Omigosh

Re: Hauptmann's money

Tue Mar 5 2002

In addition, and also in regard to the claims that Hauptmann had the "Fisch

money" (or ransom money) all along, as opposed to sometime in August, as

per his "Fisch story," there's the rather obvious (and uncontroverted)

fact that right about the time he claims to have found the Fisch money, he goes

on a bit of a spending spree.

He passes how many of these bills in how short a period of time? Buys some shoes

for his wife, if I recall correctly.

And does it right out in the open. Even gets into a dispute with a grocer who

doesn't want to accept a large bill (was it a $10?) for a small purchase, and

then wins the dispute and forces the guy to accept the bill.

When Lyle, the gas jockey, notices the gold note and comments about it,

Hauptmann doesn't make an excuse and take it back (it was evidence, after all),

but chats the guy up about how he's only got about a hundred or so left at home.

And lets the guy keep the bill. Which results in his arrest. The same thing

could have happened with the grocer, and you KNOW that guy was going to remember

Hauptmann. Which he did.

Point being, Hauptmann's bill passing is entirely consistent with his Fisch

story and entirely inconsistent with the state's theory. If the guy had the

money all along, why would he suddenly go on a "spending spree" in

August and September? I mean, he had the money all along, right?

And why pass it so openly if he knows it's Lindbergh ransom money? It doesn't

make any sense.

Unless you argue that Hauptmann was intending to get caught and use his sudden

spending spree as a set-up excuse to support the Fisch story.

Yea, that makes a lot of sense.

I know Hauptmann said and did some crazy things after he was arrested and framed

to take the fall. But that was all AFTER he was arrested and framed. Personally,

I think the guy just lost it and pretty much gave up hope after he saw what was

happening to him. He had to know he couldn't stop it and the handwriting was on

the wall.

You can't fight city hall, right?

Michael Melsky

Made-Up Shoe Box?

Fri Feb 2002

Where My Shadow Falls - Turrou p125:

In the first was found one hundred ten-dollar gold certificate wrapped in a

September 6, 1934 copy of the Daily Mirror; the second contained eighty three ten

dollar gold certificates in a copy of the Daily News dated June 25, 1934.

The Tax Dodgers by U S Treasury Agent Elmer Irey 1948

CLICK HERE TO READ Chapter Three pp. 66-87

from "Crime of the Century: The Lindbergh Case"

Please visit :

![]() Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

![]() Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

ronelle@LindberghKidnappingHoax.com

![]() Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

© Copyright Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax 1998 - 2020